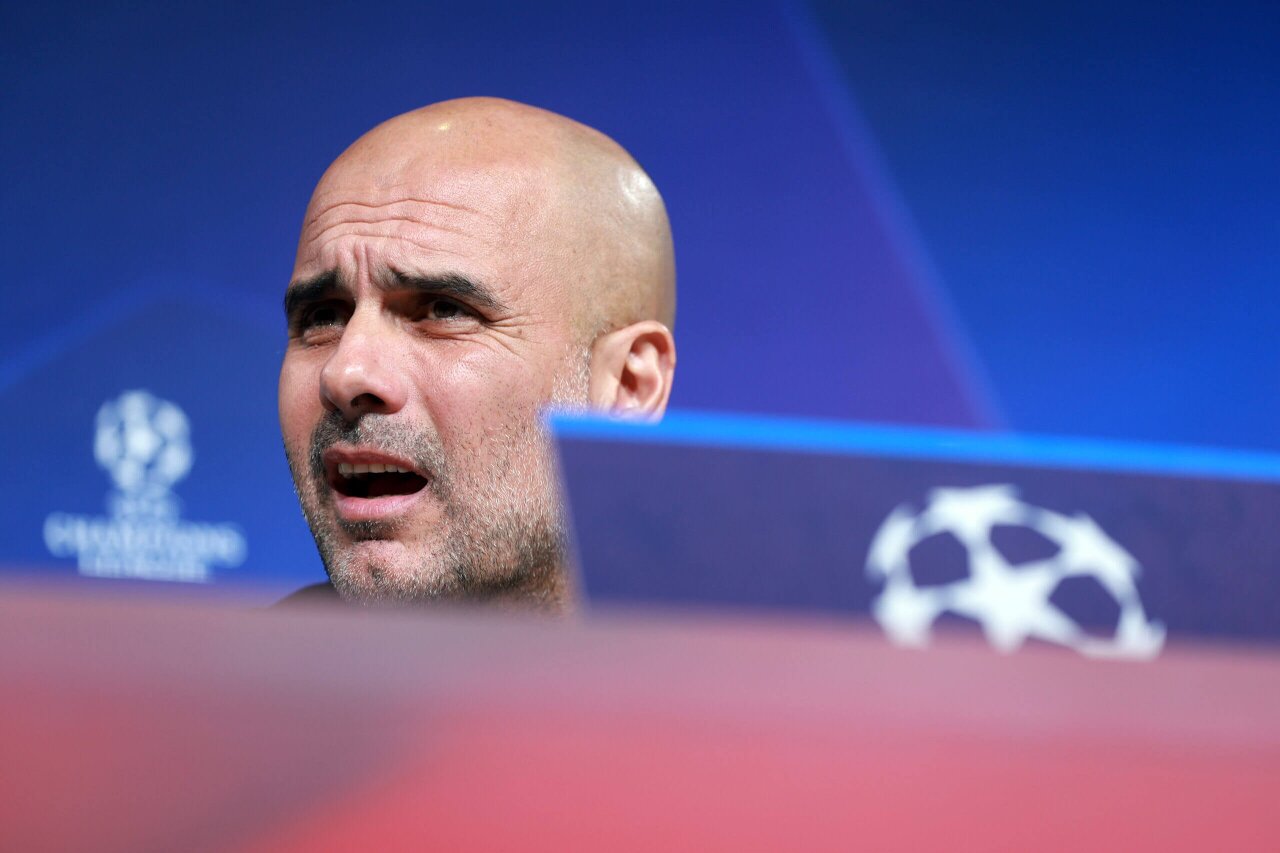

Pep Guardiola: The man behind the genius

285

Pep Guardiola sat his players down, addressing them for the first time as Manchester City manager, and he had some clips prepared.

Not, on this occasion, the freeze-frame images of the opposition’s set-up designed to highlight their strengths and weaknesses, identified after hours of painstaking analysis — sometimes literally.

There was a more overarching message he wanted to get across to the squad he had inherited from Manuel Pellegrini: the importance of togetherness in the group, of celebrating their achievements.

Pellegrini’s side had stumbled their way to the end of the 2015-16 season and only qualified for the Champions League on the final day thanks to a 1-1 draw away to Swansea City.

Guardiola had noticed that only one player in the squad, Kevin De Bruyne, was celebrating. The Belgium midfielder was not jumping for joy but he did at least have his arms in the air, pleased that City had secured their last remaining goal of the season.

Guardiola wanted to know why his team-mates had not joined him. And with that, he set about instilling a winning culture at the club that he had joined because, in part, he saw it as a major challenge of his credentials.

Fast-forward six years and City have won the lot. They have reached the promised land — the treble. During Guardiola’s reign, they have won five league titles in six years, becoming only the fifth team in English football to win three in a row. They have won the domestic treble, the first English side to do so. They won the Carabao Cup four years running, two FA Cups and, in Istanbul, the club’s first Champions League.

It is easy to look now and assert that Guardiola picked the richest team with the best facilities and that the rest was easy. The first part is hard to argue — City treat Guardiola as the jewel in their crown, ensuring he has the best conditions to work in — but back in the winter of 2015, when he was choosing his next club, he saw a lot of challenges in store at the Etihad, things the club would have to overcome if his time in charge was going to become even a fraction as successful as it has been.

He looked at their domestic rivals — Manchester United, Chelsea, Liverpool — and those on the continent — the Bayern Munich side he had just left, Real Madrid, Barcelona, Juventus — and saw clubs with a long and established history at the top level, a champion’s mentality. They had a ‘heavy shirt’, an obligation to win that had been established many decades ago.

By the time Guardiola arrived at City, they had won two titles under two different managers but, after each one, they fell back down the table.

Guardiola knew that he would have to establish that mentality himself and, given he did not expect to stay at the Etihad Stadium anywhere near as long as the seven years that he has, he would have to do it in a short period of time.

Pushing John Stones into midfield is seen within the club as the key to City’s march towards the treble: his forays into midfield and then attacking areas gave Guardiola’s side an extra option in advanced areas, one they were looking for given Erling Haaland’s limitations outside the area compared to previous options like Phil Foden and Bernardo Silva, born midfielders.

Stones first played in midfield for City four and a half years ago, in a shock 3-2 defeat at home to Crystal Palace just before Christmas 2018. That weekend, one of Guardiola’s friends was visiting Manchester and, after the match, was invited into the dressing room.

Guardiola asked his friend what he thought of Stones’ performance. The friend made some suggestions, including that the defender’s body positioning was not quite right, considering his move up the field. Guardiola agreed, and called Stones over. He then asked his friend to provide the feedback to Stones.

That is just one example of occasionally strange tactics that Guardiola has employed over the years to motivate his players. After seven years of constantly prodding his players to fight on, to give more, those tactics do not always register.

It is part of the reason why Guardiola spent 20 minutes after City beat Tottenham Hotspur in January to call out his players’ relative lack of desire. At the start of his reign, he had told his players in the dressing room, “In the press conference I will defend you until the last day of our lives — but here I’m going to tell you the truth.” Yet in January, he took the rare step of making his concerns public and all because he felt they were missing just one per cent.

By the end of the 2020-21 season, several key players had wanted to leave despite their on-pitch success: they had won the Premier League title back from Liverpool and reached the Champions League final but around five of them had grown tired of Guardiola and his methods.

That ran contrary to what is commonly understood about unhappy dressing rooms in football: traditionally, teams where players are at odds with their manager normally end up performing badly and sacking the manager. Here, City were playing their best football for a couple of years.

And what was even more astonishing is that not a single one of those players left that summer and yet they won the title again the year after. Most of them are still at the club.

It should be said that the Covid-19 lockdowns and restrictions added to the strain, and that the mood improved as life began to return to normal, but the fact remains that Guardiola has not only managed to keep his team at the top but done it largely with the same players, even those who have previously been (or, in cases, still are) tired of his methods.

A source close to the players, speaking anonymously to protect relationships, explains: “They are all aware that Pep is exhausting because he is very demanding but, by being demanding, he brings them closer to success. That’s why most of them want to continue with him.”

There are plenty who love him.

“I can’t speak highly enough of him, he’s unbelievable,” Jack Grealish says. “I don’t think anybody comes close to him. The stuff that he thinks of and comes out with, you think, ‘How have you even thought of that?’ He’s an unbelievable manager, a great guy as well, everyone loves him in the training ground and in the changing room.”

Ederson, his long established No 1 goalkeeper, explains how Guardiola’s demands look in practice. “He lives, breathes football. In every game you can see he lives it. Whether you make a mistake and he shouts at you, or you make a good pass and he shouts to applaud, he’s a guy who lives it all.

“His mind is constantly filled with thoughts, but it’s normal, we know him. When it’s time to criticise you, he criticises you; when it’s time to swear at you, he swears at you on the field; when it’s time to praise you, he praises you.

“So, he’s that kind of good coach who says whatever he has to say to you to your face.”

There are times when communication is not so forthcoming. “It’s hard to read him,” City midfielder Kalvin Phillips says. “One day he can give you the day off and the next he can be like, ‘No, you’re in until the next game’.”

That is particularly the case when it comes to his starting line-ups. “He’ll put you on the bench and doesn’t even talk to you, he doesn’t explain why, even if you have that feeling that you deserve to play,” says Bacary Sagna, who was at City for Guardiola’s first season.

While Guardiola generally does not sit down with a player and explain to them why they are not playing, what he has done is fostered a culture whereby they know that those who train the hardest and have the best attitude are the ones who start matches. “You cannot create something when people who are not playing regularly are creating problems,” he said in 2017. “Bad faces, bad behaviour from those guys — when that happens, forget about it.”

He has said that leaving players out who have trained well and shown a good attitude is the hardest part of his job, but it has set the tone, and those who do get upset with the manager know there is no use moping about it — their situation will only get worse.

When City sanctioned Joao Cancelo’s loan to Bayern in January, a shock to the outside world, it was because the Portugal defender was seen as a disruptive influence. One of the benefits of removing him was weakening a small group of dissenting voices when Guardiola was trying to restore that final one per cent.

He has adapted his approach over the years. Following City’s first two trophies of this season he allowed his players to go out and celebrate, asking only that they came back into the training ground the next day for regeneration work ahead of their remaining challenges.

In 2018, after City clinched their first title of Guardiola’s reign with five games to spare, he insisted that the players came in for training the following morning because he was desperate for the team to break the 100-point barrier. Not all of the players arrived in peak condition, but Gabriel Jesus struck in the 94th minute of the final game to rack up that century, capping one of the finest seasons in English football history.

“Pep is another thing entirely; living football becomes contagious,” Javier Mascherano, who worked with him at Barcelona, said in 2014. “He makes it that when you get up every day, you feel that what you are doing is worthwhile, that training is paramount and innate, it’s what results in your professional and personal fulfilment.

“However, he would say that everything must be earned with effort and talent.”

Although one public perception of Guardiola is that he is arrogant — and his apparently sarcastic comments play up to that — it has been said by those who know him and have studied him close up that his intensity and dedication to hard work comes both from his father, a bricklayer, and from a feeling that he is not especially talented, and needs to make up for that with a superior work ethic.

Marti Perarnau wrote in his first great Guardiola book, Herr Pep, which documented his first season at Bayern Munich, that he sat and analysed Benfica for so long that he injured his back and needed treatment.

One of the lesser-known elements of his managerial make-up is his knack for knowing when a player is in need of a rest, usually by spotting small signals in their body language. While City have an impressive sports science operation, much of the players’ game time is determined by Guardiola’s ability to realise who needs a break.

And while he does not like to have his methods questioned by journalists, he looks for assistant coaches and other figures around the team to provide alternative viewpoints or solutions to overcoming the opposition.

“He always finds new ways to play,” his former assistant Domenec Torrent tells The Athletic. “When it seems they always play the same way it’s not true, there are always little nuances that he does, in every game he’ll change a couple of things to make sure it’s different. People don’t appreciate that, because you have to be so into football to see the variations that Pep makes.

“As well as watching a lot of games, which everybody can do, Pep has a clear way of interpreting the game, always trying to control the game. That interests him a lot, dominating the games. He wants to dominate them, not wait for things to happen, dominate them. This makes him a little special.”

Bernardo Silva gave an insight into this recently: “One day if I have to play in another position, maybe it is not my best position but I know exactly what he wants with my eyes closed because I have been with him for six years.

“He doesn’t stop, he knows that the game is evolving so he doesn’t let the other teams adapt to us. Every year he tries to create something different so that the other teams don’t get used to the way we play.”

Guardiola’s sarcasm is potent.

A fine example comes from his playing days and was delivered on the pitch as his Spain side took on France at Euro 2000. Guardiola was, and is, a major admirer of Zinedine Zidane and marvelled at his talents.

During the game, as France launched a counter-attack, Guardiola had been urging his team-mates to stay on their feet, but team-mate Agustin Aranzabal brought down Youri Djorkaeff on the edge of the area. Michel Salgado congratulated Aranzabal for the foul, saying, “Well done, well done.” Guardiola was incredulous: “Well done?! Look at where the free kick is!”

Zidane duly fired it into the top corner, Guardiola turned to Salgado and said, “Well done, eh?”

After the match he made his admiration for Zidane clear: “It was a pleasure for me to play against you, one day maybe we will do it together,” he told him, in Italian, meaning every word.

Sometimes during his reign in Manchester, it has been hard to establish whether he is being serious or not, although one of the more obvious and memorable examples of overwhelming sarcasm came midway through his first season, in January 2017, after his side had beaten Burnley despite having a man sent off.

The interviewer had not had much joy getting anything out of an irritated Guardiola, who was clearly annoyed about fouls on his goalkeeper and an apparent difference in refereeing standards in English football. When it was put to Guardiola that he did not look happy with the victory, he shot back: “I’m so happy, believe me, I’m so happy. Happy New Year.”

Over the years he has used sarcasm in more humorous ways, often to broach not particularly flattering topics related to himself or his career. For years now he has been referring to himself as a “failure” because he did not win the Champions League during his time at Bayern Munich. For him, convincing the Bayern players to adopt a new style of play and continue winning while doing so — perhaps playing the best football the club had ever seen — is enough proof of his ability as a coach.

Yet because he inherited a side that had just won the treble, and he could not repeat their success in Germany, many considered his reign underwhelming. That lack of recognition clearly grates and has surfaced at different times when he says he is a failure or that his work is not good enough.

It was a similar story last year when, before a Champions League game against Atletico Madrid, he said: “Every team has their particular way to play, and you have to adapt and adjust to it, and overthink what we have to do.”

It was the first time he had mentioned overthinking, another charge levelled at him: that he makes extravagant team decisions in the biggest games that invariably go wrong (when they go well it is usually ignored).

“In the Champions League, I always overthink, I always create new tactics and ideas, and tomorrow you will see a new one,” he added, in equal parts dry and sarcastic.

“I overthink a lot, absolutely it’s fair. That’s why I’ve had very good results in the Champions League. It would be boring, my job, if all the time I had to win the same way.”

What people say about him clearly registers, which is an interesting development because it had always been said that he never paid any attention to what was written about him — even in-depth, well-informed and favourable coverage like Perarnau’s two books about his time at Bayern.

It has got to the stage now where it has become an open secret that he has an anonymous Twitter account and likes to see what is being said. When City beat RB Leipzig 7-0 in March, he referenced Twitter and fans’ pre-match fears about his starting line-up. That was the night that he bizarrely brought up Julia Roberts’ visit to Manchester United’s Old Trafford stadium years earlier.

“I am a failure in the Champions League, I’m sorry,” he said. “I’m going to explain a secret. Julia Roberts came to England a few years ago in the period when Manchester United were not good, we were better, and she came to Manchester United, she didn’t come to us. Even if I win the Champions League, it cannot make up for Julia Roberts not coming to see us.”

He had earlier admitted to German television that he had enjoyed a large glass of red wine after the final whistle and, given he still does not eat much on matchdays because he is too nervous, it must have gone straight to his head.

Normally, though, he picks his moments to talk about failure and overthinking because he is, in his way, poking fun at his detractors.

When he was young he hoped everybody would like or at least appreciate his work and initially took criticism personally. As he matured he realised that people would dislike him no matter what, and that nothing could change that. In recent years, he has grown to embrace some of that hate, getting to the stage where he can make fun of it.

These days there is a lot more flourish to those “Happy New Year” comments from his first season in charge, when his frustrations were evident. He has learned to handle adversity much better — publicly at least — and even use it to his advantage.

He once called Jose Mourinho the “puto amo” — the fucking boss — of press conferences, but no doubt some of Guardiola’s finest work has been done in front of the world’s media. Arguably, it is there that he looks most at home.

Indeed, that “puto amo” afternoon was in 2011 before Barcelona’s Champions League clash with Real Madrid, the third of four Clasicos in 18 days, across three competitions. In the wake of Madrid’s victory in the Copa del Rey final and constant baiting by then manager Mourinho, he sought out “Jose’s camera” and shot back.

“We worked together for four years,” he said. “He knows me, I know him and that’s all. If he wants to go by things written after the Copa del Rey by friends from the press or Florentino Perez then fine. If that matters more than our relationship, then that’s up to him.”

It was not so much what he said on that occasion but that he said it at all: it was not his style. Many suggested he had cracked under Mourinho’s pressure, yet his Barcelona players greeted him with a standing ovation.

At City, he has used potentially difficult situations to change the narrative. In that first season, after his side had been eliminated from the Champions League by Monaco in the round of 16, he faced a busier-than-normal press auditorium prepared for an inquest.

In those days it felt like the walls were closing in: this would be the first trophyless season of his career. Plenty of people had wondered whether English football may be too physically demanding for his possession-based style, and those complaints about fouls on his goalkeeper did little to change that view.

“Exceptional is my career,” he said at one point. “I’m sorry, that is exceptional.”

He had no doubts about his abilities and on that day the English media first got to grips with another of the traits that come out in the difficult moments: defiance.

The intervening years have proven him correct, but he has still had to field questions about larger subjects that would normally be outside of a manager’s remit: allegations of financial wrongdoing by City.

If losing to Monaco in the Champions League felt seismic, it was nothing compared to being banned from the competition for two years by UEFA, European football’s governing body in charge of the competition. The shock news had raised suggestions that Guardiola and his players would leave the club in their droves.

“Unless they sack me, which can happen, I will not leave,” he insisted. “Why should I? I love this club, I like to be here, and after we have seen the sentence we will focus on what we have to do.”

When that ban was later overturned by the Court of Arbitration for Sport, Guardiola came out swinging.

“What happened in recent years, how many times people came to our club to whisper about us. I would like to say to these kinds of people: look into our eyes and say something face to face, and then and go to the pitch and play on the pitch. They lost off the pitch. They have to go on the pitch and try to beat us.”

At another point, he said: “The opponents always deserve my respect and credit. And Arsenal, I have all the respect for what they are on the pitch — not much off the pitch – but on the pitch, a lot.”

It may be hard to imagine now, with a large banner of him triumphantly smoking a cigar often raised at the Etihad, but there was a time, even after a couple of Premier League titles, when Guardiola was not quite loved in the same way that Roberto Mancini, the man who delivered their first league title in 2012, was.

Mancini tied a blue and white scarf around his neck and fought back at Manchester United boss Sir Alex Ferguson in a similar way that Guardiola had done to Madrid’s Mourinho. Mancini not only took City to the top but represented what the fans wanted to see and hear from their manager, too.

Guardiola has not always done that. He has criticised the atmosphere and attendances at the Etihad on several occasions, even in the recent past, with the aim of giving his players an edge in upcoming big matches, but he often alienated supporters to some extent.

Mancini was combative, which appealed to some City fans’ sensibilities, whereas Guardiola always seemed more refined, even sophisticated. Different, certainly.

Although any negative feelings over attendance comments never lingered for long, it meant that he was not always revered as much as his predecessor.

In recent years that has changed completely, and it has been through press conferences as much as on the pitch that has helped change the mood. That post-CAS press conference, and another one this season after City were charged with 115 breaches of Premier League rules, allowed him to come out fighting, to defend his club and endear himself even further to fans.

“I can assure you, more than ever I want to stay,” he said, combating an assumption that he would leave. “Sometimes I have doubts, seven years already is a long time. Now I don’t want to go.”

He also called out Tottenham chairman Daniel Levy, who was a hot topic behind the scenes at City that week because they believe him to be a driving force behind the charges. And while discussing the possibility of City being stripped of their trophies, Guardiola asked if Steven Gerrard’s famous slip against Chelsea in 2014, which helped send the title to Manchester while Pellegrini was manager, was City’s fault.

He later apologised for that comment, but it shows that when his back is against the wall, all bets are off. In many instances these are topics that the club would rather Guardiola did not discuss but, rather than toe a party line, he is happy to field question after question, if he has not broached the subject.

That combination of fighting back against those who have criticised City, showing his passion for the club and turning them into the most dominant team on the planet has elevated him to God-like status at the Etihad.

Away from the cameras he is personable, but can be awkward.

The general rule seems to be that if there is a match coming up, which invariably there is, he is consumed by football. Even those close to him say he can be difficult to talk to if it is not about the match at hand or at least some other footballing topic.

Before this season’s FA Cup final he gave his players two days off, but spent most of that time watching clips of their Champions League final opponent, Inter.

Even so, it is not always as linear as pre versus post-match. A few days before the 2019 FA Cup final, he attended the launch of a book about him written by Catalan journalists Luis Martin, an old friend of his, and Pol Ballus, now of The Athletic. For the most part, he sat at the back of the room next to his wife, Cristina, who he had met when he was 18, and was not especially talkative with the journalists present or anybody else.

It may be obvious that he would not want to speak to journalists away from ‘the office’ but it stands out as strange because, a couple of days later, he invited regulars to his press conferences and held court, appearing completely at ease and greeting everybody with a warm handshake and, in some cases, a hug.

After City sealed their passage to the Champions League final by beating Real Madrid 4-0, in what was probably the club’s best-ever performance, he planted a kiss on the cheek of the head of communications, Simon Heggie, and was later pictured with members of the club’s board and other confidants, including his brother Pere and former Argentina president Mauricio Macri, holding up four fingers.

He is happy to pose for photographs with fans around Manchester and regularly eats out in the city centre at haunts such as Tast, which he partly owns, or increasingly at MUSU MCR, a Japanese restaurant.

When he first arrived in Manchester he played golf in Audenshaw — which he struggled to pronounce — in the eastern part of the city, far from the posher hotspots of Hale or Alderley Edge.

And if he is more comfortable around friends and family, that would make him no different from most of the population but the theme seems to be that, no matter the company, he is by far the most comfortable in a setting where football, discussed with people on his level, is the focus.

He has welcomed many visitors to the City training ground over the years, whether friends or influential figures in football or other sports, and these visits are generally pencilled in for the day after a match, when the training sessions are light and Guardiola is usually more relaxed.

But each of those people make the trip to Manchester knowing that, if City lose the match, the arrangements will be cancelled. In that case, he wants to focus on what had gone wrong and try to improve it for next time.

As long as City are doing well, life is calmer. But during matches, even winning does little to ease the pressure and sometimes even the celebrations do not last too long: he normally turns to the stand behind him to pump his fists in the direction of his son, Marius, but during City’s pivotal victory against Arsenal in April he remembered that Ederson had made the wrong pass in the build-up and shouted at him. While the pass had led to his side’s opening goal, it was still the wrong option.

On the touchline, in the heat of battle, his irritations and insecurities are there for the world to see. When the opposition launch a counter-attack or prepare a set piece, he crouches down in the corner of his technical area, as close to the scene as possible, until the danger has passed. If a refereeing decision goes against his side he will make sure the fourth official knows about it.

He refuses to rise to the bait when asked about referees and their decisions but he has plenty to say during the match, away from the microphones. “I found him affable, warm and polite when it isn’t a game day,” one former Premier League first-team coach tells The Athletic. “On game days, he is a terrible loser in the tunnel and can come across as aggressive and stroppy when he loses.

“Most people in the industry would say he is the worst loser in football. I should say, that does not make him a bad person at all because being a bad loser in sport is normal. But he can be pretty graceless in defeat when he is beaten and it was never about the other team being great, it was always something else.”

Guardiola is careful not to come across that way in public: for example, after beating Fulham in April, he criticised the length of the grass but made a point of saying that he only did so once they had won; had they lost he would not have wanted it to be seen as an excuse.

The length and condition of the grass has been a fascination of his throughout his career; on his first day at Bayern, he went to the Allianz Arena and measured the pitch itself and the length of the grass. He said that the grass needed to be 3mm shorter and needed to be wetter.

His relationship with City’s ground staff can be strained due to his constant demands about the length and condition of the grass: at one point recently he made a series of comments about the state of the pitch at the Etihad that flew under the radar of the wider public but not those inside the club. There have been differences of opinion because in the winter ground staff like to grow the grass slightly longer to allow for the extra wear and tear, but that takes it above Guardiola’s ideal limits.

These things are not done to be difficult: if the ball gets held up in the grass by even a fraction of a second it can disrupt Guardiola’s teams’ carefully-detailed rhythm.

Now, with the season out of the way, he will disappear for the summer, going on holiday before returning to Barcelona to be with Cristina, who moved back there in 2019, and spending a lot of time playing golf, as he did during his playing days in Qatar.

He has developed a deep bond with Manchester over the years, though, according to Perarnau. The author says the terrorist attack at the Manchester Arena in 2017, which killed 22 people, left an “indelible mark” on him. Cristina and their two daughters had left the Ariana Grande concert one minute before a bomb was detonated.

“I remember his emotion as he listened to the poet Tony Walsh read, in a cracking voice, the vibrant poem Choose Love at a vigil in Albert Square,” Perarnau writes. “The emotion of the resounding, ‘This is the place…’, the forcefulness of, ‘Always remember. Never forget. Forever Manchester. Choose love’.

“It was on that day Pep began to feel truly Mancunian.”

Earlier this season, in the wake of the Premier League charges, he delivered an impassioned speech to his players.

“Everything we have won, guys, has been on the pitch, always. I love the club and I love you too, let’s go.”

For Guardiola, everything comes back to what has been done on the pitch. It is little wonder considering his first message to his players seven years ago and his attempts to create a winning culture at a club without one, but it is worth remembering now, in their hour of glory.

It is why he bristled at the suggestion that City’s success has been easy to come by, or even that the Champions League was the missing piece. Sure, he knew City needed European glory to satisfy the outside world, but it would not have changed his opinion of his work in Manchester.

“I agree with most of the people who said that we’ve not achieved in Europe, we’ve not won the Champions League and maybe they are right,” he said in April. “To get the recognition of everyone in the world outside we need to conquer Europe.

“Is it going to happen? I don’t know. So far what we’ve done here makes me incredibly happy. First of all, we had fun. We did many, many good things, that’s my feeling. But whether it is enough doesn’t matter. I could not care less.”

There can be no doubts now.

(Additional contributors: Pol Ballus and Raphael Honigstein; Top image: Getty Images, design by Eamonn Dalton)

'Total Football Way' 카테고리의 다른 글

| FC 바르셀로나 한지 플릭 감독의 축구 철학과 전술 변화 분석 (1) | 2025.03.18 |

|---|---|

| 리오넬 메시의 드리블 리듬: 축구 GOAT의 과학적 분석 (1) | 2024.07.26 |

| [한준, 전술조각모음] 빌드업: 경기를 만드는 6가지 방법 (0) | 2018.01.08 |

| THE WORLD OF JOHAN CRUYFF (0) | 2017.02.08 |

| Andres Iniesta: How to boss the midfield (1) | 2017.02.02 |