Of all parts of the body, the hand is by many considered to be the hardest to draw. We all have stories of how, early on, we would keep our characters' hands behind their backs or in their pockets, avoiding as much as possible the task of tackling hands. Yet paradoxically, they are our most readily available reference, being in our field of vision every moment of our lives. With just one extra accessory, a small mirror, we can reference hands from all angles. The only real challenge, then, is the complexity of this remarkably articulated organ: it's almost like drawing a small figure onto a larger one, one doesn't know where to start.

In this tutorial we will deconstruct the hand's own anatomy and indeed demystify it, so that when you look at a hand for reference, you can make sense of it as a group of simple forms, easy to put together.

I use the following abbreviations for the fingers:

- Th = thumb

- FF = forefinger

- MF = middle finger

- RF = ring finger

- LF = little finger

Basics of the Hand

Here’s a quick look at the bone structure of the hand (left). In blue, the eight carpal bones, in purple, the five metacarpal bones, and in pink, the 14 phalanges.

As many of these bones cannot move at all, we can simplify the basic structure of the hand: the diagram on the right is all you really need to remember.

Note that the actual base of the fingers, the joint that corresponds to the knuckles, is much lower than the apparent base formed by flaps of skin. This will be important to draw bending fingers as we will see later.

Based on the above, a simple way of sketching the hand is to start with the basic form of the palm, a flat shape (very much like a steak, but roundish, squarish, or trapezoidal) with rounded angles, then attach the fingers :

If you have a hard time drawing fingers, it’s very helpful to think of them, and draw them, as stacks of three cylinders. Cylinders are easy to draw under any angle, taking away much of the headache of drawing fingers in perspective. Observe how the bases of the cylinders are exactly the folds you need to draw when the finger bends.

This is important: The joints of the fingers are not aligned on straight lines, but fall onto concentric arches:

In addition, fingers are not straight, but bend slightly towards the space between MF and RF. Showing this even subtly gives life to a drawing:

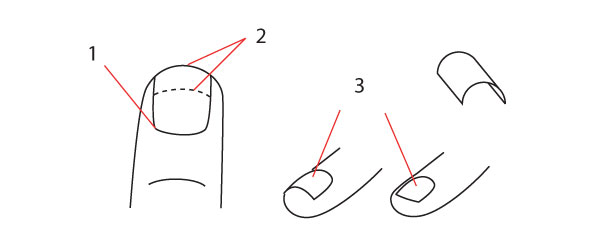

Let us not forget the fingernails. There is no need to always draw them, indeed they are a degree of detail that only looks right when the hands are seen sufficiently close up, but we are not usually taught how they should look, and because of this, I for one couldn't make them look right for a long time. Here are some notes on the fingernail:

- The fingernail starts halfway up the top joint of the finger.

- The point where fingernail detaches from flesh varies: some people have it all the way at the edge of the finger, others have it very low (dotted line), so in their case the fingernails are wider than they are long.

- Fingernails are not flat, but shaped much like roof tiles, with a curvature ranging from extreme to very slight. Observe your hand and you may find that this curvature is different for each finger – but this level of realism is unnecessary in drawing, fortunately.

Proportions

Now, taking the (apparent) length of FF as our base unit, we can roughly put down the following proportions:

- The maximum opening between Th and FF opening = 1.5

- The maximum opening between FF and RF = 1. The MF can be closer to either without affecting the total distance.

- The maximum opening between RF and LF opening = 1

- The maximum angle between Th and LF is 90º, taken from the very base of the Th’s articulation: the fully extended LF is aligned with it.

I said "roughly" because these do vary with people, sometimes a lot, but remember that deviating from the norm on paper can look wrong. If in doubt, these measurements will always look right.

Details

The basic shape is only one challenging aspect of the hand; the other may be the detailing of folds and lines. Who hasn't been frustrated by drawing a hand and not being able to get all these lines to look right? Let's look at fold lines and some measurement details:

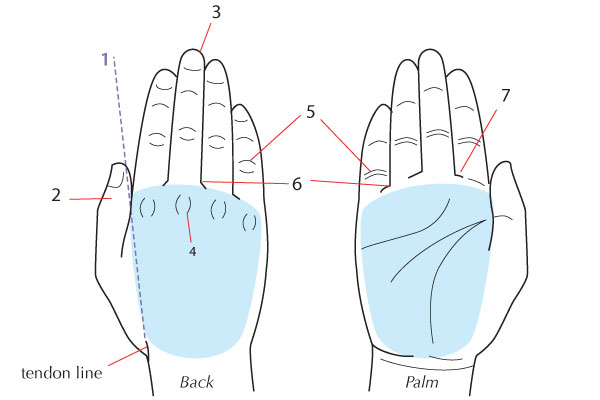

- The virtual extension of the inner line of the wrist separates the thumb from the fingers. A small tendon line may mark the junction of wrist and hand.

- When fingers are close together as above, the thumb tucks a bit under the palm and is partially hidden.

- The FF or RF as sometimes almost as long as the MF.

- The folds that mark the knuckles are elliptical or like parenthesis, but when the hand is flat as above they are not pronounced (unless someone has protruding knuckles, which happens on much-labored hands) and can be drawn as mere dimples.

- The folds of the finger joints show elliptically on the back side, but they fade when the fingers are bent. They show as parallel lines on the palm side, but they are more pronounced at the lower joint – typically you wouldn't use two lines for the upper joints.

- From the back, the lines of the fingers extend down to the limit of the palm, which makes the fingers look longer from the back.

From the inside, the lines are shorter because the top of the palm is padded, so the fingers look shorter on the palm side. - The lines of the fingers end in are drag lines (these short horizontal dashes) on both sides, and on both sides these drag lines all point away from the MF.

Note also, in the diagram above, how the fingernails are not drawn fully but indicated in a subtle way appropriate to the overall level of detailing (which is rather higher than necessary, for purposes of showing all the lines). The smaller the hand you're drawing, the less detail you want in it, unless you want it to look old.

I didn't mention the lines of the hand above, so let's take a look at them closely here:

- The most visible lines in the palm: the so-called heart, head and life lines, are where the skin folds when the palm is cupped. Unless your style is very realistic, there's no need to draw others, it will look excessive.

- Don't confuse the life line with the contour of the thumb, which becomes visible under certain angles such as the one on the right. The life line is almost concentric with the contour of the thumb, but see how much higher on the palm it originates – the (true) base of the FF, in fact.

- From the side, the padding at the base of each finger appears as a series of curved, parallel bulges.

- These fold lines wrap halfway around the fingers. They are accentuated as the finger bends.

- There is a small bump here on the extended finger due to skin bunching up. The bump disappears when the finger bends.

Now, what do we see when the hand is extended and seen sideways?

- Outside, the wrist line curves out into palm base, so the transition between the two is marked by a gentle bump.

- The bottom of the hand looks flatter from the outside than it does from the inside, although the thumb base may still be visible.

- From the outside, the RF’s last joint is fully exposed because the LF is set well back.

- From the inside, a little or none of the MF can be visible, depending on the FF’s length.

- Inside, the wrist line is covered by thumb base, so the transition is more abrupt and the bump more important.

Note also that when seen from the outside, the palms shows another, new contour line. It starts at the wrist and, as the hand turns more, joins up with the LF line, until it covers up the Th base:

Range of Motion

Detailed articulation implies movement, and the hands move constantly. Not just for functional uses (holding a mug, typing) but also expressively, accompanying our words or reacting to our emotions. It's therefore no surprise that drawing hands well requires understanding how the fingers move.

The Thumb and Fingers

Let's start with the thumb, which works alone. Its real base, and centre of movement, is very low on the hand, where it meets the wrist.

- The natural relaxed position leaves a space between the Th and the rest of the hand.

- The Th can fold in as far as touching the root of LF, but this requires much tension and quickly becomes painful.

- The Th can extend as far as the width of the palm, but this also implies tension and gets painful.

The other four fingers have little sideways movement and mainly bend forward, parallel to each other. They can do this with a certain degree of autonomy, but never without some effect on the nearest fingers; try for instance to bend your MF alone, and see what happens to the rest. The Th alone is completely independent.

When the hand closes into a fist and the fingers all curl together, the whole of the hand maintains a cupped shape, as if it was placed against a large ball. It’s just that the ball (here in red) gets smaller and the curvature stronger:

When the hand is fully extended (on the right), the fingers are either straight or bend slightly backwards, depending on flexibility. Some people’s fingers can bend back 90º if pressure is applied against them.

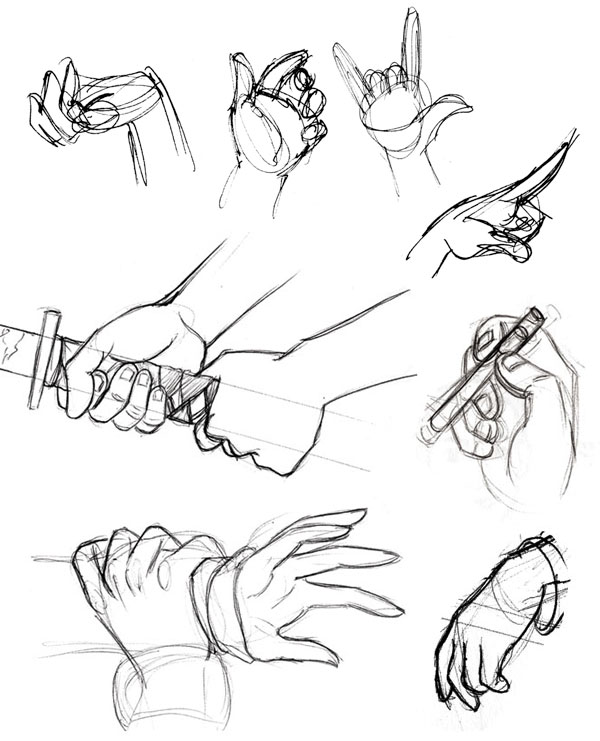

The fully closed fist is worth a detailed look:

- The 1st and 3rd fold of the fully bent finger meet, creating a cross.

- The 2nd fold appears to be an extension of the line of the finger.

- Part of the finger is covered by the flap of skin and the thumb, a reminder that the whole thumb structure is outermost. You can make your FF slip outside and cover the flap of skin, it's anatomically possible, but it is not a natural way to form a fist.

- The MF's knuckle protrudes most and the other knuckles fall away from it, so that from the angle shown here, the parallel fingers are visible from the outer side, not from the inner side.

- The 1st and 3rd fold meet and create a cross again.

- The thumb bends so that its last section is foreshortened.

- The skin fold here sticks out.

- When the hand makes a fist, the knuckles protrude and the "parenthesis" are visible.

The Hand as a Whole

When the hand is relaxed, the fingers curl slightly – more so when the hand is pointing up and gravity forces them bent. In both cases, the FF remains straightest and the rest fall away gradually, with the LF being the most bent. From the side, The gradation in the fingers makes the outer 2 or 3 peek out between FF and Th.

LF frequently “runs away” and stands isolated from the other fingers – another way of making hands look more natural. on the other hand, the FF and MF, or MF and RF, will often pair up, “sticking” together while the other 2 remain loose. This makes the hand look more lively. RF-LF pairings also occur, when the fingers are loosely bent.

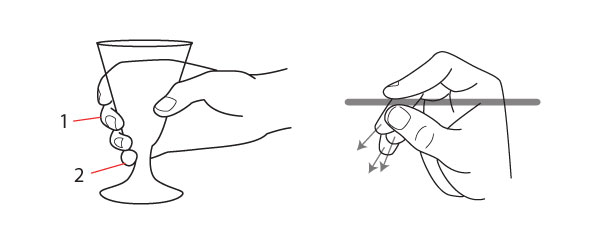

Since the fingers are not the same length, they always present a gradation. When grasping something, like the cup below, the MF (1) wraps the most visibly around the object while the LF (2) barely shows.

When holding a pen or the like, MF, RF and LF curl back towards the palm if the object is held only between Th and FF (pick up a pencil lightly and observe this). If more pressure is applied, MF participates and straightens up as it presses against the object. Full pressure results in all the fingers pointing away as shown here.

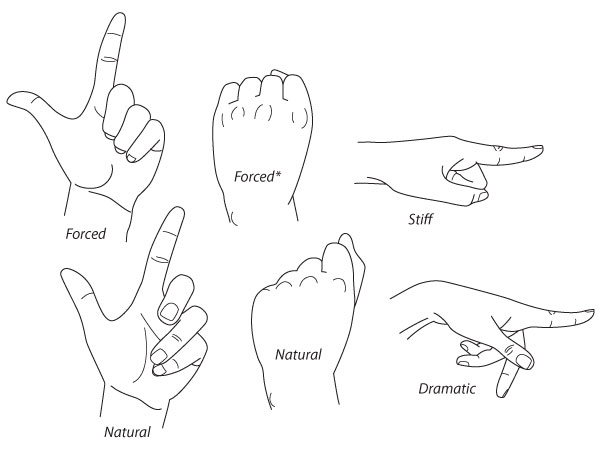

As we have seen, the hand and wrist are remarkably articulated, each finger almost having a life of its own, which is why hands tend to stump the beginning illustrator. Yet when the hand starts to make sense, we tend to fall into the opposite trap, which is to draw hands too rationally – fingers carefully taking their places, parallel lines, careful alignments. The result is stiff and simply too tame for a part of the body that can speak as expressively as the eyes. It can work for certain types of characters (such as those whose personality shows stiffness or insensitivity) but more often than not, you’ll want to draw lively, expressive hands. For this you can go one of two ways: add attitude (i.e. add drama to the gesture, resulting in a dynamic hand position that would probably never be used in real life) or add natural-ness (observe the hands of people who aren’t thinking about them to see the casualness I’m referring to). I can’t possibly show every hand position there is, but I give below examples of constrained vs. natural/dynamic hand:

*Note in this particular case – trained fighters will always hold their fingers parallel while punching (as in the forced position), otherwise they may break their knuckles.

Diversity

Hands vary individually just as much as facial features. Males's hands differ from female's, young from old, and so on. Below are some existing classifications, but they don't cover the whole range of characters a hand can have. Character is a good word because it's most useful to draw hands as if they were characters with their own personality: delicate, soft, dry, callous, uncouth and so on. (See Practice Time)

Hand Shapes

This is really about the proportion of fingers to hand: