The European Club Association met earlier this month with Europe's elite club competition on its agenda, while there is evidence to suggest that fans want change

![]() COMMENT

COMMENT

The ECA met earlier this month for its General Assembly in Paris. one of the topics for discussion was the future for its clubs in Uefa’s European club competitions. The ECA renewed last year its three-year Memorandum of Understanding with Uefa covering the participation of its clubs in Uefa competition for the period 2015-2018. That deadline is now looming on the horizon and member clubs are in discussion about what might come next.

The question is: will it be more of the same again or a European Super League?

Before the previous MoU - covering 2012-2015 - was signed, Rummenigge threatened to pull ECA clubs out of Uefa’s competitions and start its own unless calls for reform were met. The ECA demanded, among other things, that the international match calendar be truncated and clubs receive fair compensation and insurance payments when players are injured on international duty.

Last year, the ECA also signed a new Memorandum of Understanding with Uefa covering the period 2015-2022. As a result of that, two ECA club representatives are due to join the Uefa Executive Committee with full voting rights at the Uefa Congress in May after initially joining with observer status last year.

"In the future, the ECA will not only be directly involved in the shaping of European football through its participation in the Uefa Executive Committee, but also benefit from higher funding," Rummenigge said. "All clubs will benefit from a higher share of the increased Champions League and Europa League revenues for 2015-2018, in particular the Europa League participants."

By and large Uefa has worked hard to appease the hugely influential ECA. The threat of a rebellion, which would have sunk the Champions League as we know it, delayed.

The issue, though, of a European Super League has never truly gone away and is again shaping conversations at the top levels of the European game. Uefa may well run the Champions League but the ECA is a mighty cabal and it is that body, and not solely Uefa, which will decide the future of continental football.

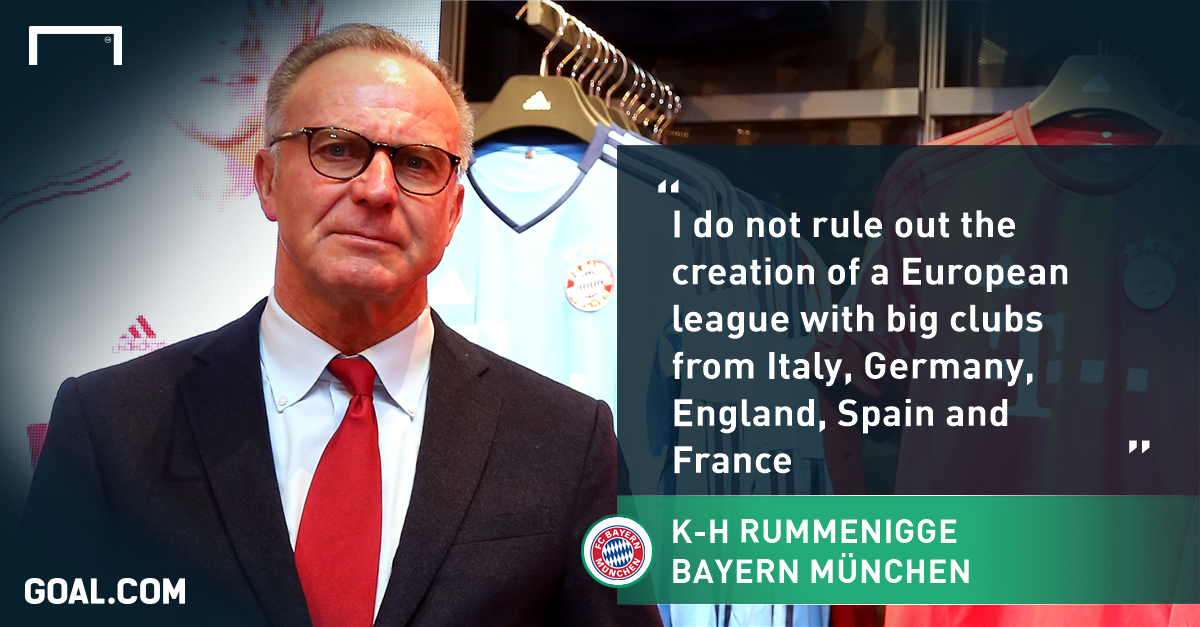

The Super League idea is clearly one which Rummenigge supports given how forcefully he has spoken on the subject. As recently as January of this year – at a panel discussion at the Universitá Commerciale Luigi Bocconi – he said: “I do not rule out the creation one day of a European league featuring the big clubs from Italy, Germany, England, Spain and France.”

Just on a competitive level alone, a cursory glance around the top of those European leagues would provide evidence of why a new format along those lines might appeal to clubs and indeed fans. Barcelona, Bayern Munich and Paris Saint-Germain will again win their respective national leagues at a canter. In Italy, Juventus are getting there too; their draw against Bologna on Friday was the first time they dropped points in Serie A since October. Leicester City might well be bucking the trend but the natural order will return to the Premier League sooner rather than later – with Manchester City and Chelsea on top and Arsenal and Manchester United following closely after. The season there is a freak.

By taking selected super clubs continental, the ECA envisages an NFL-style bonanza which pits the best against the best – week after week – and ensures massive incomes all round. ECA clubs must look across the Atlantic and weep with jealousy. All 32 American Football franchises appear on the Forbes list of the 50 most-valuable sports teams compared to just seven of the world’s soccer clubs. The current NFL television deals are together worth around $5 billion per-season. That is the kind of booty Rummenigge and the ECA want to access.

England’s Premier League is leading the way in television money and there is simply no chance of any other national league ever matching its current £5.1 billion domestic broadcast deal. That contract, signed last year, means that clubs finishing 20th in the Premier League from next season on will be entitled to some £97m (€125m) in combined prize and broadcast monies. Winning the Champions League currently brings in a maximum of around €55m. Those sums cheapen the honour of being kings of Europe. It’s not that money should be halted in the Premier League but clubs outside England need a way to conjure similar sums.

“We talked about the Super League,” ECA vice-chair Umberto Gandini admitted to the press after the General Assembly. “Every three years, we analyse with Uefa what is working well. We discuss modifications, amendments, changes or improvements that we could make. This is the phase where we are now.

"We are starting a review process of the Champions League and working with Uefa to see which improvements we can bring in to have the most attractive football product every year. The process will last six to nine months maximum but it is clear we have to take into account all the measures to make it more and more attractive.

"There is not any kind of understanding that we have to change the Champions League. We will listen to the main actors of the competition and Uefa itself and find out what is best. It may be just a slight change to the access list; it may be many aspects of the competition that can be reviewed and adjusted."

That language means the Super League is not yet imminent but it’s not off the table either. Whether it would be a replacement for the Champions League as a continental competition to sit alongside domestic leagues or else a supranational league which would remove the elite clubs altogether from their domestic surroundings permanently is still up for debate. Whatever happens down the line, the “slight change to the access list” could be the first step towards locking in the big teams. Talk is already swirling around that certain clubs will be guaranteed participation to the group stages of a reformed tournament at the expense of those outside the elite band.

“What we’re seeing, quite worryingly, is that there are moves within the movers and shakers of European football to try and reshape the Champions League, potentially remove the champions’ route and make it not just harder, perhaps impossible, for the champion clubs of smaller nations to participate in the Champions League,” the Scottish Professional Football League chief executive Neil Doncaster told BBC Radio 5 Live earlier this month.

“I think this is a very sinister development. The likes of Celtic, Rangers, Aberdeen, Ajax, Porto – these are huge brand names, huge clubs with great histories and great global fan bases. And there’s the possibility that some may try and limit or remove their access to the Champions League.”

There are suggestions, therefore, that the clubs at the top of the pyramid are unhappy with the current set-up. They want more high-impact matches and more money and it might just be that supporters would like a change now too.

Talking to fans has brought the realisation that they have grown weary of the elite clubs steam rolling the group stages with few genuinely meaningful fixtures, of a seeded knockout draw which prevents the heavyweights meeting early and of the drawn-out format which means action takes an age to complete. The current viewing figures echo that.

“Over the last five seasons we have seen Champions League audiences fall 38%,” Sky Sports chief Barney Francis wrote last summer when Sky handed over its Champions League broadcast rights in the UK to BT Sport. “Last season, we saw our lowest ever average match audience and not a single European game appeared in our top 40 football matches.”

This season the figures read even worse. The Champions League, evidently, is losing its grip on popular consciousness, especially in England where domestic matches remain a far bigger draw. To compound that reality, a recent report in the The Telegraph revealed that the decision to move Champions League coverage from terrestrial broadcaster ITV and subscription channel Sky Sports to BT Sport in a £900m deal has seen audiences plummet.

Around 4.5 million people combined watched the Champions League play-off games broadcast last season on ITV and Sky Sports. For a comparable match this season, Manchester United’s play-off matches against Club Brugge, the average peak viewing numbers sunk to around one million on BT Sport’s free Showcase channel and European football channel. Around five million people combined watched the final on ITV and Sky Sports in the UK last season; time will tell how BT’s figures stack up against that.

That five million figure pales in comparison to when an English side was last in the final. Around 9.7 million tuned in to watch Chelsea beat Bayern Munich on penalties in 2012. There is no replacement for native success but there is no real financial necessity for English clubs to prioritise the Champions League given the disparity in income in that competition and what’s on offer at home.

Uefa has faced down this kind of threat before with drastic implications for what once was a straight up champions-versus-champions knockout competition. Back in 1987, Real Madrid and Napoli were drawn together in the first round of the European Cup. one of the richest television territories for the competition was about to lose its representative. It was decided that more would have to be done to safeguard the progress of the most lucrative teams. Hence, the Champions League was born and the carve up began.

The Champions League was expanded in line with clubs' wishes in 1997 when Uefa recognised the threat posed by the mooted Media Partners super league. Using the Italian company's interest in a breakaway as leverage, the biggest clubs in Europe initiated an expanded tournament. Again, the threat worked.

But how long is it sustainable? For European clubs who see even England’s mediocre teams grow richer and richer? For the fans who would dearly love to see more compelling matches? For Uefa which has to appease its biggest clubs at every turn?

A Uefa spokesperson told Goal: "Uefa constantly reviews the format of its competitions in close consultation with stakeholders, including the European Club Association. There are no concrete proposals on the table at this stage as we have just begun a new three-year cycle (2015-18) for club competitions."

The format is not necessarily what makes the Champions League compelling. Whatever method is used to decide which two teams play in the final come early summer is largely irrelevant. What it’s about is that night, that trophy. There have been tweaks to the format in the past – for better for worse – but the team who goes home with the cup is classified as the best in Europe.

'Football World' 카테고리의 다른 글

| [한준 이슈] 레전드 그 이상, 축구는 크라위프 전후로 나뉜다 (0) | 2016.03.25 |

|---|---|

| 새 축구 대통령 인판티노, 그는 누구인가? 새 축구 대통령 인판티노, 그는 누구인가? (0) | 2016.02.28 |

| JACK REYNOLDS: THE FATHER OF AJAX AMSTERDAM (0) | 2016.02.19 |

| HOW AMSTERDAM CHANGED THE WORLD OF FOOTBALL FOREVER (0) | 2016.02.19 |

| What does the Chinese Super League's ambition mean for MLS? (0) | 2016.02.16 |